Geomorphic Mapping

This page lays out some of the features that we typically map as part of our monitoring protocol. For each feature there is a brief description, some lines of evidence that can be used to hep accuratley map them, as well as a list of attributes that will need to be created for each (which is described in a bit more detail in this video).

Valley Bottom

-

Create a polygon shapefile named valley_bottom.shp

-

Fields:

-

area_sqm: decimal > area($geometry)

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

-

Digitize the valley bottom

-

Field calculate necessary fields

What is this layer? Valley bottom is the stream/river channel and the adjacent low-lying areas, also known as the contemporary floodplain. The spatial extent of the valley bottom is defined as the area that could plausibly flood during the current flood regime. THIS SETS THE EXTENT OF YOUR DIGITIZING. None of the remaining shapefiles from this point on should exceed your valley bottom.

In some instances, the drone imagery may not include enough of the lateral extent of the valley bottom. In these cases, it is okay if your valley bottom is wider than the ortho, just use some other imagery to help you. Remember: the valley bottom sets the extent of your digitizing not the orthoimage.

Note: the valley bottom is unlikely to change over time (at least not within the window of time that we are concerned with). So, once a valley bottom has been mapped for a given site, simply export that shapefile as the valley bottom for future repeat flights. In other words, THE VALLEY BOTTOM EXTENT SHOULD BE THE SAME FOR ALL REPEAT FLIGHTS FOR A GIVEN SITE.

Lines of Evidence:

-

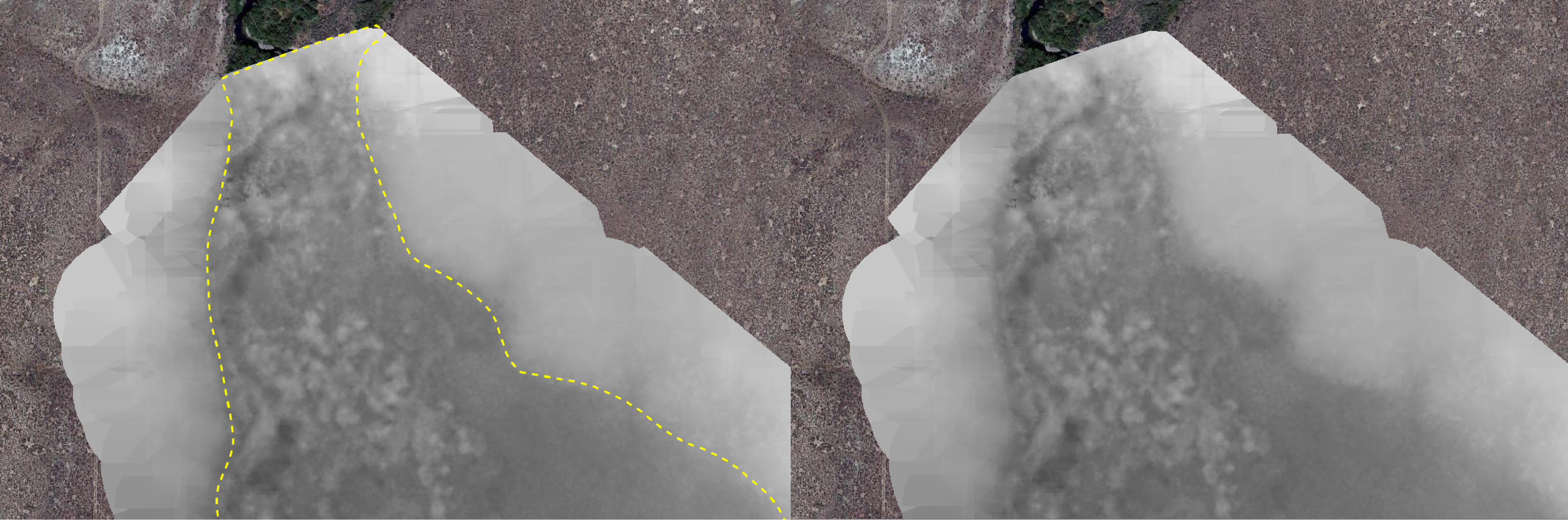

In sufficiently resolved elevation rasters such as ones derived from drones, you may see a “lip” where the elevation changes from flatter valley bottom to steeper hill slopes rapidly.

-

You may see a change from dense vegetation to sparse vegetation because the slope is too steep to support vegetation.

-

If there is a VBET run for your area, that is also a good line of evidence.

Active Channel

-

Create a polygon shapefile named active_channel.shp

-

Fields:

-

area_sqm: decimal > area($geometry)

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > waterbody

-

-

Digitize the channel edge, this includes bars and islands that are in the channel

-

Calculate fields

What is this layer? Active channel is the area of the channel that is modified by average stream discharge. This means it includes non-wetted features such as islands and bars that are located within the bankfull of a channel.

Lines of Evidence:

-

Clear signs of scouring

-

Channelization

-

Bars

-

Elevation raster may show the channel

-

Breaks in the tree line

-

Greener areas beside the channel

-

Generally no non-aquatic vegetation, in non-perennial systems there may be some grasses growing in the channel during the dry season

Riparian

-

This feature will be the same extent as your valley_bottom.shp so to create this shapefile, simply export your valley_bottom.shp and save it as riparian.shp.

-

Fields:

-

area_sqm: decimal > area($geometry)

-

type: string > ‘riparian’ or ‘upland’

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

-

Digitize the riparian areas within your riparian.shp and enter the type as “riparian”, and ensure trace is enabled for areas that abut the valley bottom.

-

From here, select all the areas labeled as riparian and then clip them from the upland polygon by clicking the “Clipper”

icon from the clipper toolbar or the “Cut with selected polygon” tool from the Digitizing Tools plugin. (You can also do riparian in step 3 and then upland in step 4; do what makes most sense to you)

-

Remove the active_channel extent from your riparian layer. To do this, merge your riparian.shp with your active_channel.shp using the “Merge Vector” tool. Select the active_channel portion of this layer and delete. Overwrite this updated layer with your old riparian.shp.

-

Calculate fields

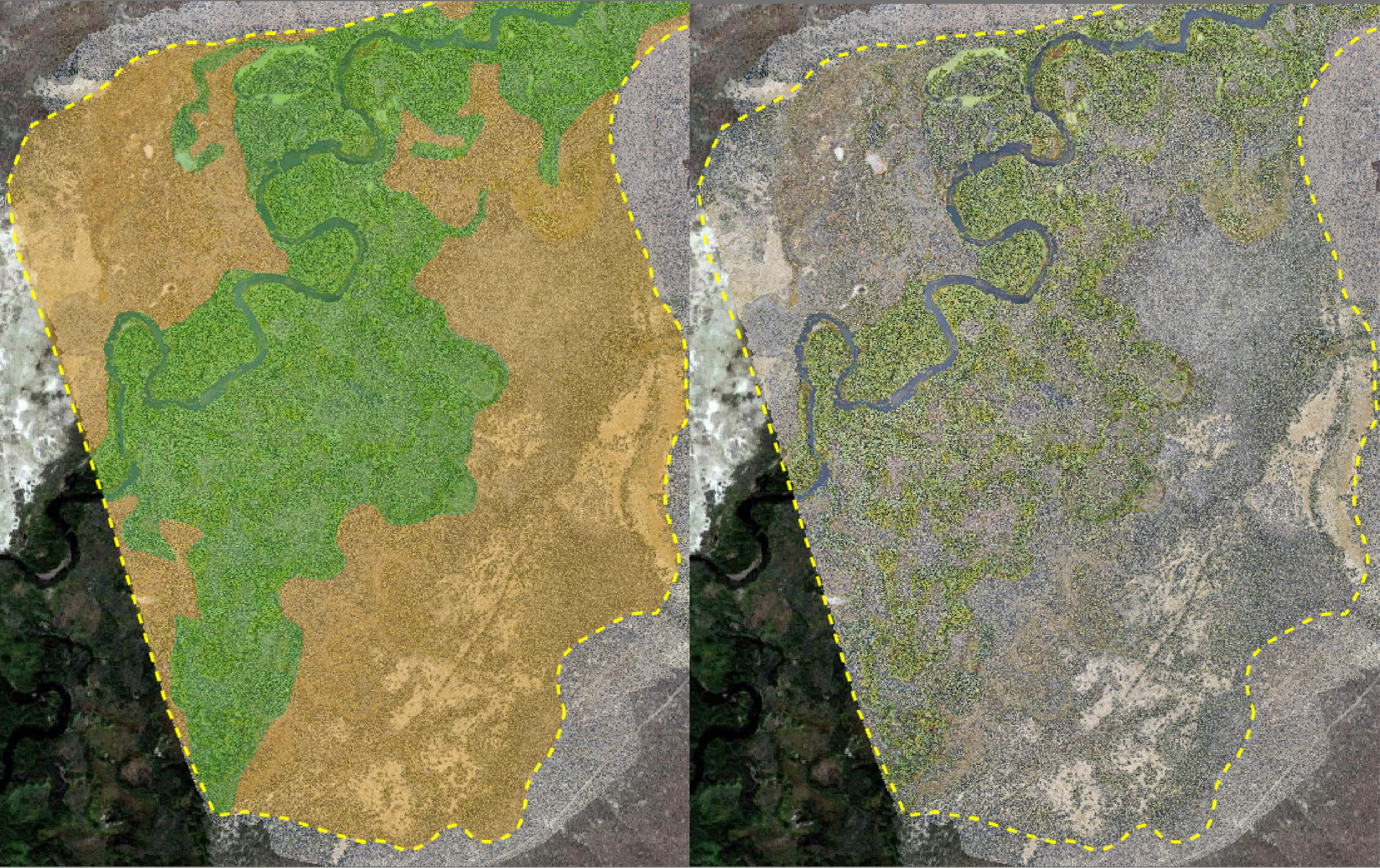

What is this layer? The riparian layer represents the extent of riparian vegetation (willows, cottonwood, tamarisk, etc.) and upland vegetation (sagebrush, conifer, rabbitbrush, etc.) We use vegetation as an indicator of the portions of the floodplain that are potentially being inundated under the current flow regime. Previously we had tried to map the “active floodplain” but the lines of evidence were weak. Now we map riparian as a way to approximate the current floodplain activity without making any false claims.

Lines of Evidence:

-

Perennial riparian vegetation

-

In desert systems, riparian can sometimes be the only greenery in the valley bottom

-

If the riparian stands are dead, this does not count as riparian

-

Suppression of upland vegetation growth indicates riparian

-

NDVI raster if available

Inundation

-

Duplicate the active_channel layer by exporting it and saving as inundation.shp. If you prefer you can make a polygon from scratch rather than reshaping and building on the active_channel shapefile.

-

Fields:

-

type: string > ‘free_flowing’, ‘overflow’, or ‘ponded’

-

area_sqm: decimal > area($geometry)

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

-

Using the reshape and add ring tools, modify the polygon to fit where there is water. This is also a good place to use clipper or split features tools because each of these inundation types is mutually exclusive.

-

Calculate fields

What is this layer? This layer shows where the water is within the valley bottom; in other words, what is currently being inundated at the time the imagery was taken. Free-flowing is water that is flowing in the channel unobstructed, ponded is a structurally forced pooling, generally caused by a beaver dam, and overflow is water that is being structurally forced onto the floodplain and out of the channel or a structurally forced secondary channel; overflow is often associated with intact dams.

Lines of Evidence:

-

Are there surrounding structures that may be affecting the flow?

-

Is there water in the system?

-

Dams can back up water much further than you may expect.

Dam Crests

-

Create a new line shapefile named dam_crests.shp

-

Fields:

-

dam_state: string > ‘intact’, ‘breached’, or ‘blown_out’

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

-

Trace the crest of each observed dam, in cases where the dam has damage, trace where the crest would be if it was intact

-

Calculate fields

What is this layer? This layer traces the top crest of a dam to show the location, extent, and state of the dam. The options for dam_state are intact, where the dam is intact, breached, where the dam has some damage but is still ponding water at a lowered level, and blown_out where there is structural damage the whole height of the dam so it is not ponding water. Ponded water should be traced along the dam crest line if a dam crest is present, then the free flowing after should trace that same dam crest line.

Lines of Evidence:

-

Ponded water

-

Dams are generally convex with the current

-

Does the dam have a mattress? A mattress is branches that lay on the downstream side of a dam parallel to the current to help dampen the strength of any overflow and prevent scouring at the base of a dam.

-

Be careful to make sure this isn’t a woody debris accumulation.

-

“Bathtub” ring of mud around the perimeter of the dam indicating a relatively recent breach

-

Area of concentrated flow at the location of the breach

Channel Segments

-

Create a line shapefile named channel_segments.shp

-

Fields:

-

type: string > ‘primary’ or ‘secondary’ note: there should only be 1 primary channel with the rest being secondary channels

-

length_m: decimal > length($geometry)

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

-

Digitize along the center of the channels you’ve previously digitized, and ensure snapping is enabled so that each channel segment connects to each other.

-

Calculate fields

What is this layer? This layer simply represents the number of channel segments within a site and can be an indicator of complexity. The primary channel is the segment that runs through the main channel, while secondary segments run along side channels and areas where the channel may split due to structures in the stream or islands.

Lines of Evidence:

- The primary channel is typically the larger channel. If there are two channels that are similar sizes, use the channel that follows the google maps trace of the river and has a name.

Confluences and Difluences

-

Create a point shapefile named confluence_difluence.shp

-

Fields:

-

type: string > ‘C’, ‘D’, or ‘C/D’

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

lat: decimal > $y

-

long: decimal > $x

-

-

Digitize confluences (C) and difluences (D) where there are channel segments that meet and split

-

Calculate fields

What is this layer? This layer maps flow patterns in a channel. Confluences are where water meets and difluences are where water splits. C/D can be used where one area has both a difluence and a confluence, you can also place a C and a D point at these places if that makes more sense to you rather than one C/D point.

Lines of Evidence:

-

Channel segments converge or diverge

-

Islands

-

Determine flow direction by looking at channel heads and slope. Higher elevation is generally upstream and channel heads generally point upstream.

Structures

-

Create a point shapefile named structures.shp

-

Fields:

-

type: string > ‘live’, ‘lwd’, ‘inorganic’, ‘jam’, ‘bda’, or ‘pals’

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

lat: decimal > $y

-

long: decimal >$x

-

-

Digitize features by placing points atop structures where you observe them.

-

Calculate fields

What is this layer? This layer can contain low-tech restoration structures and other structures that are structurally forcing flows. This means that flows in some way are being modified by these structures. Modification of course exists for every size of structure down to a grain of sand if you get pedantic however, for the sake of digitizing, flow modification should be visible from aerial imagery. This can include bank erosion, new channels, split flows, pond formation, etc. Live means vegetation growing in the channel, inorganic can be things like boulders, a jam is woody debris that is channel spanning and ponding water, lwd is large woody debris in the channel such as a fallen tree, BDAs or beaver dam analogs are human-made structures meant to mimic the function and form of a beaver dam, PALS or post assisted log structures are restoration structures being held in the channel by posts. Dams should not be digitized in this shapefile because they are already digitized in dam_crests.

Lines of Evidence:

-

Structurally forced flows

-

Signs of geomorphic modification

-

PALS may have small circles in the structure visible from aerial imagery, those are the posts

-

Shapefile indicating location of LTPBR structures

Valley Bottom Centerline

-

Create a line shapefile named vb_centerline.shp

-

Fields:

-

date: date > now()

-

waterbody: string > ‘waterbody_name’

-

length_m: decimal > length($geometry)

-

-

Run the ‘Points along geometry’ tool using your valley_bottom.shp as an input and a distance of 5m. Leave the output as a temporary layer.

-

Use this new points temporary layer as the input for the “Voronoi polygons tool”

-

Using the snapping and trace tools in QGIS, digitize the line that runs down the center of the valley bottom.

What is this layer? This line shows the center of the valley bottom. This can be used to determine sinuosity. It’s useful for data processing after digitizing

Lines of Evidence:

Voronoi polygons layer